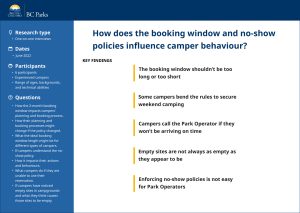

Exploring Asian History in Provincial Parks

Categories:

Contributions of Asian Canadians are woven into B.C.’s landscape. As part of Asian Heritage Month, BC Parks wants to reflect on historic places found in provincial parks and protected areas. These sites tell stories of strong communities and racial discrimination. Before diving deeper into exploring history, BC Parks wants to acknowledge that Asian culture and history includes many diverse cultures, languages, and backgrounds. The following two examples provide a small window into Japanese Canadian and Chinese Canadian history.

Japanese herring salteries at Saysutshun (Newcastle Island Marine) Provincial Park

Fishing provided a livelihood for some of the first Japanese immigrants in B.C. and their descendants. One provincial park that holds this history is Saysutshan (Newcastle Island), off the coast of Nanaimo. A Japanese community grew around Nanaimo and in Departure Bay around fishing for herring and salmon. At the beginning of the 19th century, they established salteries for their catch and a large shipyard that built and repaired boats. Saysutshan (Newscatle Island) was a seasonal site with clustered fishing camps and salteries. These were processing sites for export to Asia, mostly Japan, and then in later years China. As the Japanese fishing industry grew in Nanaimo, four of these salteries burned down in 1912 and arson was suspected. Further, by the early 1920s, restrictions were put in place as to how many licenses were given out, where they could fish and how many Japanese decedents could be employed in their own salteries.

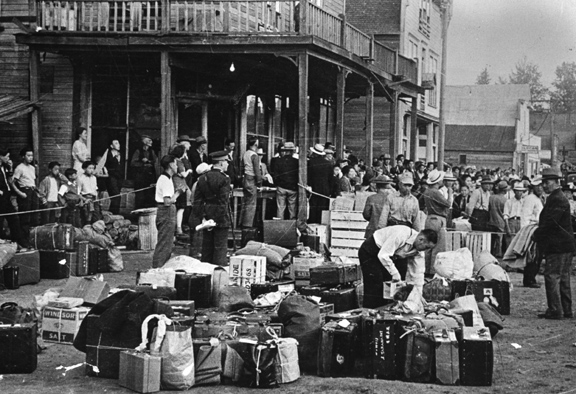

In 1941 (during WWII), 1,200 Japanese-Canadian fishing boats were confiscated. By 1942, around 22,000 Japanese Canadian citizens had to sell or were stripped of their property and forced to move to internment camps in the interior or further east. The Japanese fishing community of Nanaimo and Saysutshan (Newcastle Island) Provincial Park was not an exception. The internment camps were mostly previous ghost towns or hastily built villages that were overcrowded with inadequate plumbing and insulation. It was not until five years after the war that Japanese Canadians were allowed to move back to the coast and re-establish their once prosperous fishing towns and villages.

Cement Factory at Gowlland Tod Provincial Park

Chinese and other Asian Canadian immigrants often received work in dangerous industries such as mining, factories, and building railways. Compared to European employees, they were paid less, had communal living spaces, and held dangerous positions. Some remnants of this history can still be found in Gowlland Tod Provincial Park, which is about half an hour drive from Victoria. From 1904, Tod inlet used to be home to a community of Chinese and South Asian Canadian workers who worked for the Vancouver Portland Cement Company. This site was associated with a limestone quarry and clay mine. Today, visitors can walk the well-maintained trail system historically used by workers back then. You can still see the building foundations, pillars of the wharf, and even find tools and artifacts! When the cement plant closed in the early 1920s, many of the workers became employed at Butchart Gardens. Butchart Gardens is recognized as a national historic site and is internationally known.

Both these sites, like many others across B.C., represent the historic sacrifices endured by Asian Canadians. Despite adversity and discrimination, Asian communities stayed strong and grew. B.C. is made of a diversity of cultures and ancestries that have contributed to what our province is today. This month we encourage you to learn more about Asian heritage.